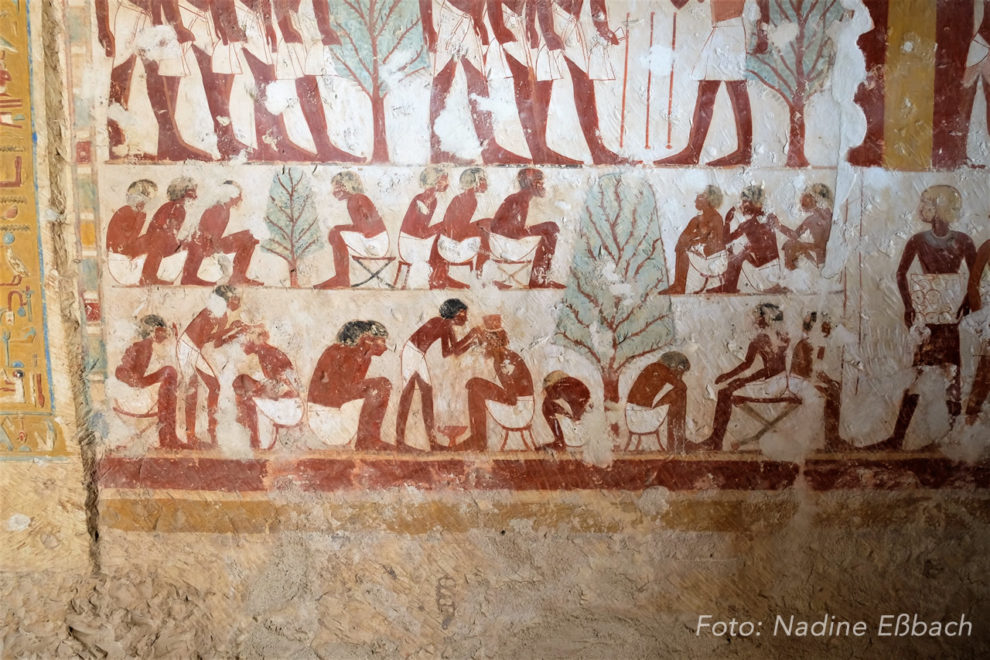

Even after more than 3000 years, the frescos in the tombs of the high-ranking Egyptians still glow as colorfully as ever. However, in contrast to the paintings in the far better-known tombs of the Valley of the Kings, these depict not only scenes from the afterlife, but also – and, indeed, principally – daily life in this world. The images portray the bustling activity along the fertile banks of the Nile and provide insights into the life and death of the people who lived there, their everyday joys and sorrows, and their often hard circumstances.

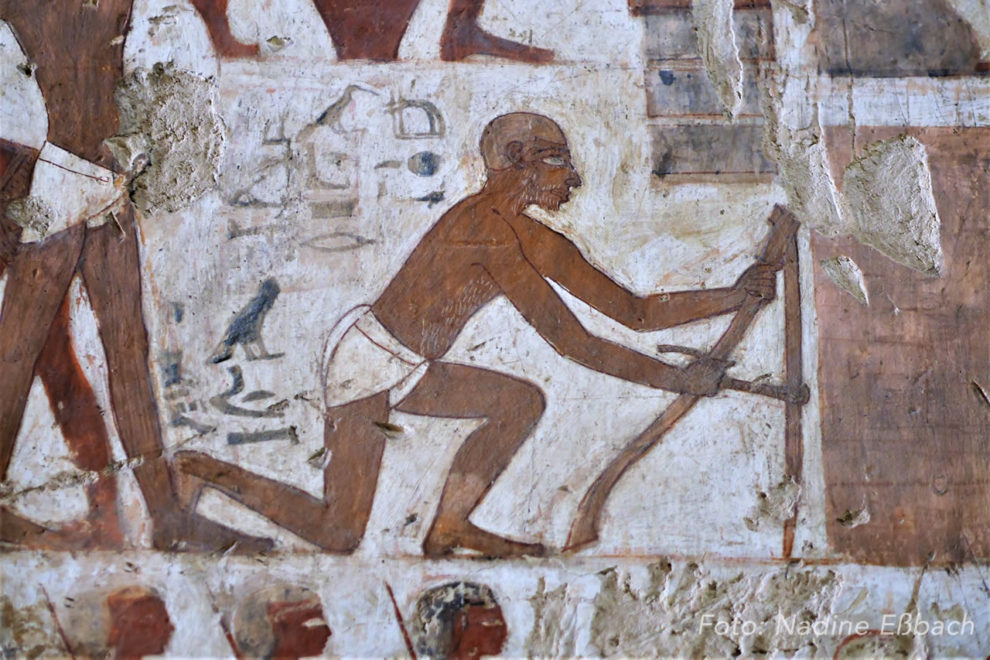

The tombs’ inhabitants and their families are generally depicted as ageless, with luxuriant hair and wrinkle-free faces. Opportunities to look behind these smooth masks are rare, but careful observers will discover an unshaven mason with white chest hair in the tomb of Rekhmire or lamenting women in the tomb of Ramose, their bare breasts succumbing to age or gravity.These occasional signs of age are joined by indications of sickness and suffering: one of the barbers in the tomb of Userhat is marked by polio, one leg clearly shorter than the other. An image in the tomb of Menena is less tragic, but no less moving, showing one girl extracting a thorn from the foot of another.

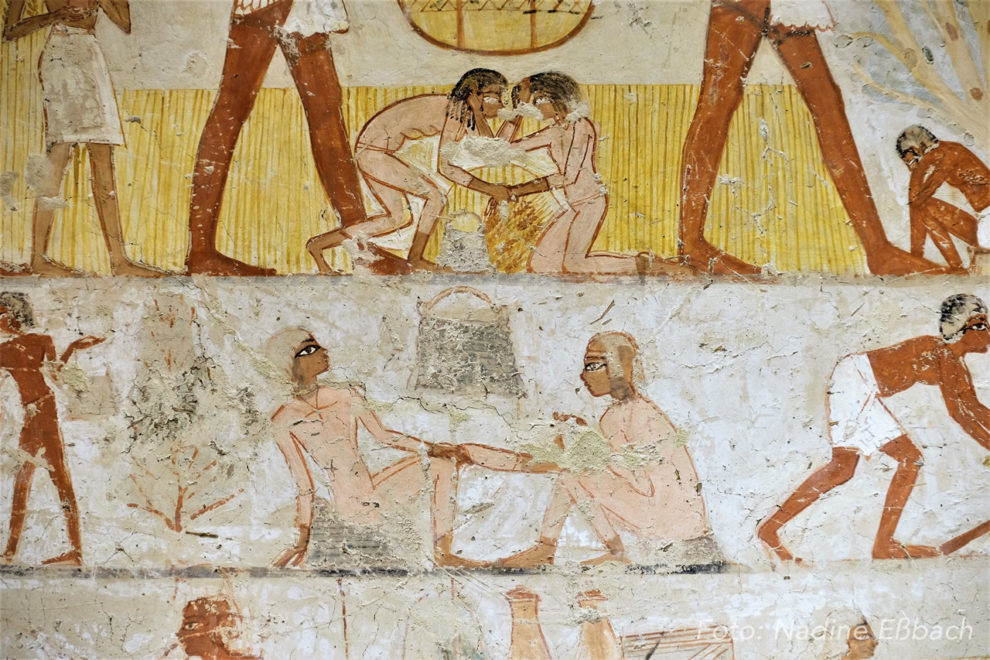

But life on the Nile was not always hard. There were also plenty of opportunities for leisure – clearly enthusiastically embraced by the winemakers in the tomb of Userhat, who can be seen sampling the sweet grape juice as they work the wine press. Their unsteadiness and slurred speech is captured here for eternity.